We certainly hear a lot more about the religious right than we do about the religious left. This past week, for example, a number of conservative religious leaders, including Franklin Graham, son of famous evangelist Rev. Billy Graham, called for a day of prayer for the president, saying that no president has been attacked more than Donald Trump. Graham and other evangelical religious leaders have been outspoken in their support for Trump before and since his election. President Trump himself stopped by a large evangelical church in Virginia this past Sunday for a brief visit and interaction with the pastor during the worship service.

The idea that this large and influential "religious right" could be countered by a "religious left" has bounced around for a long time, but has gained currency this year -- in part because of the self-identified religiosity of Democratic presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg, the mayor of South Bend, Indiana. Buttigieg has been forthright in discussing his religious faith and how it leads him to support substantially different policy goals than those usually backed by religious conservatives.

Buttigieg describes himself as a very religious Episcopalian and has been one of the few Democratic candidates to bring religion back into the political conversation from a liberal perspective. As Buttigieg , "The left is rightly committed to a separation of church and state ÔÇŽ but we need to not be afraid to invoke arguments that are convincing on why Christian faith is going to point you in a progressive direction. ÔÇŽ When I think about where most of Scripture points me, it is toward defending the poor, and the immigrant, and the stranger, and the prisoner, and the outcast, and those who are left behind by the way society works."

A Look at the Numbers

One of the major challenges faced by any politician interested in a religious left movement is the indisputable fact that there are fewer Americans today who are both highly religious and liberal than there are Americans who are both highly religious and conservative.

This conclusion is based on my analysis of 2018 ║┌┴¤═° data among non-Hispanic whites. I will return to the challenge of reaching black Americans below. Blacks are the most religious of any major racial or ethnic group in the country and strongly oriented to voting Democratic, with exit poll data showing that about nine in 10 voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016.

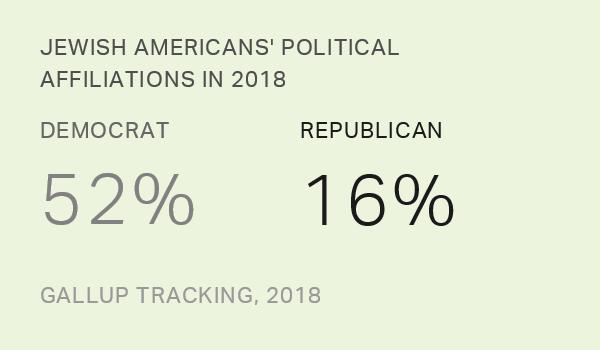

I estimate that about 20% of non-Hispanic white Americans are both conservative and highly religious (defined as those who attend religious services weekly or almost every week and for whom religion is important in their daily life) and thus are, broadly speaking, the "religious right." By contrast, only 4% of non-Hispanic white Americans are both liberal and highly religious, or the group that would constitute the "religious left." More broadly, 52% of white conservatives are highly religious, compared with only 16% of white liberals.

In short, the potential for political activation of highly religious white voters -- most importantly in reference to the looming 2020 presidential election -- appears significantly higher on the right side of the ideological spectrum than on the left.

What about the influence of the religious left within the Democratic Party? Here again, the potential impact of religion for candidates seeking their party's nomination appears lower than is the case in the Republican Party. My estimate is that about 23% of white Democrats are highly religious. The majority of these highly religious white Democrats are ideologically moderate and conservative, which wouldn't fit the definition of a classic "religious left." (Only 9% of white Democrats are highly religious and liberal -- the description, it appears to me, that would best fit Buttigieg.) This suggests that Democratic candidates seeking to activate support among highly religious white members of their party would need to move more to the center of the ideological spectrum.

By contrast, 51% of white Republicans are highly religious, and 40% are highly religious and conservative, the analog to the religious right.

Implications for 2020 Presidential Race

Volumes have been written about the long-standing connection between conservative ideology and religiosity -- including a while back. There are many postulated causes for the relationship, such as hypothesized and to simultaneously value religion and conservatism. Others argue that that fits their ideology or political identity. And there is little question that Republican candidates and leaders, including President Trump, have taken care to nurture the religion/politics relationship by emphasizing policies that fit with the dominant themes evident in evangelical beliefs.

If Buttigieg or other Democrats attempt to focus on activating support among religious white Democrats in the primaries, they will have only a small base to work with, as we have seen. White Democrats are less religious than Republicans are, leaving fewer individuals to target.

Democratic candidates would have a larger target group if they reached out to moderate or conservative white religious Democrats, as I noted above. But this does not fit well with Buttigieg's positioning. In theory, this approach might work for others of the 24 or 25 candidates who are attempting to position themselves as more moderate than Buttigieg, but it's unlikely that even these Democratic candidates are going to take the type of conservative positions on key values issues such as abortion or gay rights that could be important to more moderate or conservative religious voters.

Blacks, who constitute over a fifth of all Democrats, will play a key role in candidate selection in several early primary states and can be a significant factor in the general election in key states. Black Democrats are much more likely to be highly religious than white Democrats are, and black Democrats are also much more likely to be ideologically moderate or conservative. This again leaves a liberal candidate like Buttigieg in a tough position if he attempts to emphasize his personal religiosity in an effort to gain black support.

Emotions are a real key to politics, providing the underpinning that keeps individual voters sticking like glue to specific political ideologies and candidates. Emotions are also a key to generating enthusiasm and turnout in political campaigns. Since religion has a significant emotional component, it can be a potent political variable (as Republican candidates have well learned). But the basic fact of political life today -- that religiosity is more correlated with conservatism than liberalism -- is unlikely to change dramatically between now and next year's election.

One final note. The religiosity variable I'm using in this analysis is based on self-reported religious service attendance and self-reported importance of religion in one's daily life. It's possible that some voters who do not attend services and say "religion" is not important are still spiritual -- and could therefore respond positively to blandishments from a religious left perspective.