Story Highlights

- Americans' mood on key metrics worse than in other recent midterm election years

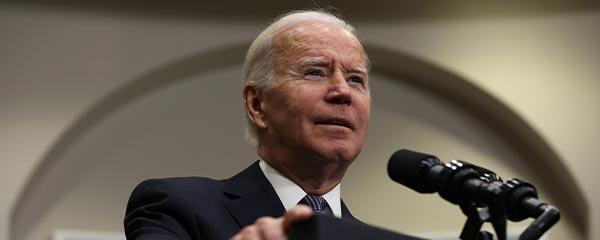

- President Biden's low job approval rating points to Democratic seat losses in 2022

- Party identification and leaning evenly split in third quarter

WASHINGTON, D.C. -- The political environment for the 2022 midterm elections should work to the benefit of the Republican Party, with all national mood indicators similar to, if not worse than, what they have been in other years when the incumbent party fared poorly in midterms.

Heading into Election Day, 40% of Americans approve of the job Joe Biden is doing as president, 17% are satisfied with the way things are going in the U.S., 49% describe the health of the economy as poor (compared with 14% saying it is excellent or good), and 21% approve of the job the Democratically led Congress is doing.

Current ratings of the U.S. economy and national satisfaction are the lowest ║┌┴¤═° has measured at the time of a midterm election over the life of these polling trends, starting in 1994 and 1982, respectively. Congressional and presidential job approval are near their historical low marks.

The following sections discuss the relationship between midterm election outcomes, historically, and each of these four polling indicators, as well as party affiliation.

President Biden's Job Approval Rating

The political peril of a party led by an unpopular president is apparent in the fact that the incumbent president's party has lost seats in every midterm election when his approval rating has been below 50%. Seat losses in the House of Representatives for unpopular presidents' parties have averaged 37 since 1946.

Biden's 40% job approval rating is higher than only one other recent president at the time of a midterm election -- George W. Bush in 2006, at 38%. Further back in history, Harry Truman also had sub-40% approval ratings in both of his midterm elections, in 1946 (33%) and 1950 (39%).

In other recent midterm years -- 2010, 2014 and 2018 -- between 41% and 45% of Americans approved of the job the president was doing, with seat losses ranging from 13 to 63 in those years.

Only two presidents since World War II saw their party gain House seats in midterms -- Bill Clinton in 1998 and Bush in 2002. Those presidents had 66% and 63% approval ratings, the highest and tied-for-second-highest preelection midterm ratings in ║┌┴¤═°'s trends.

Although Democrats are poised to lose seats in the House, the losses may not be as large as a 40% job approval rating, by itself, would predict. That's because the Democratic Party currently holds a bare majority in the House (220 seats), compared with the much more robust majorities (over 250 seats) they had going into the 1994 and 2010 midterms when Republicans picked up more than 50 seats.

Despite Obama's 44% rating in 2014, Democrats suffered minimal losses (13 seats) that year because they were already the minority party (holding 201 seats) after their major losses in 2010 and modest gains in the 2012 election.

Congressional Job Approval Rating

║┌┴¤═° finds that 21% of Americans approve of the job Congress is doing, essentially the same level of approval as in each of the past four midterm elections.

In 1994, 2010 and 2018 -- all years when Congress' approval rating was between 21% and 23% and the president's party was in the majority -- the incumbent's party lost between 40 and 63 House seats. In 2014, even with approval of Congress at 20%, the Democratic Party lost only 13 seats -- again explained by Democrats' weak starting position that year with House Republicans already in the majority.

In years when congressional approval was significantly higher, the president's party suffered minimal losses or even gained seats.

It is clear that when congressional job approval is low, generally speaking, voters are more likely to hold the president's party accountable than the majority party in Congress. In the nine recent midterm elections in which congressional job approval was at or lower than 35%, the president's party lost seats in all of those elections, including five in which his party also held the majority in Congress. In the four elections in which Congress was unpopular and the president and House majority were controlled by different parties -- 1974, 1982, 1990 and 2014 -- the House majority party gained seats each time.

U.S. Satisfaction

This year marks a new low for satisfaction with the way things are going at the time of a midterm election. The 17% of Americans who are satisfied is five percentage points lower than the prior low, 22% in 2010.

Greater midterm seat losses tend to occur when satisfaction is low. Recent examples are 1982 (24%), 1994 (30%) and 2010 (22%). By contrast, the president's party suffered smaller losses or even gains in years when satisfaction was high, including 1986 (58%), 1998 (60%) and 2002 (48%).

As with congressional approval, voters tend to take out their dissatisfaction more on the president's party than on the majority party in Congress when there is divided government.

Ratings of the Economy

The economy promises to be a key voting issue in this year's elections, as 46% of Americans mention some aspect of the economy as the most important problem facing the country. The top two specific issues are inflation (20%) and the economy in general (18%).

Americans' concern about the economy is a reflection of its perceived health -- 14% describe its current condition as excellent or good, 37% as only fair, and 49% as poor. The 35-point gap between positive and negative evaluations of the economy is the worst ║┌┴¤═° has measured at the time of a midterm election (with trends going back to 1994), surpassing the -31 gap in 2010.

Economic ratings tend to be less strongly related to midterm election outcomes than other mood indicators are, though views of the economy certainly influence how Americans rate the job that political leaders are doing and whether they are satisfied with the way things are going in the country.

Generally positive evaluations of the economy in 1994, 2006 and 2018 were not enough to overcome weak job approval ratings for Presidents Clinton, Bush and Trump, respectively -- as well as Congress' low approval ratings those years -- suggesting political leaders were being evaluated on factors besides the economy. However, Biden's weak job approval today is in line with Americans' dim view of the economy, perhaps tethering his party's chances this election to the issue more than usual.

Party Affiliation

Americans' party identification and partisan leanings have been closely divided in recent months, as they were in the third quarter of most recent midterm election years. In the third quarter of 2022, an average 45% of U.S. adults identified as Democrats (28%) or leaned Democratic (17%), while 44% identified as Republican (27%) or leaned Republican (17%).

Typically when third-quarter party affiliation is close to evenly split, as in 1994, 2002, 2010, 2014 and 2018, Republican candidates have fared better. The major exception was 2018, when Democrats had a strong showing in the elections, perhaps because of Trump's unpopularity and the unusually high turnout that year.

By contrast, in the two years when the Democratic Party had sizable advantages in party identification, 1998 and 2006, Democrats picked up seats in Congress.

Implications

Midterm elections usually favor the party that is out of power -- and if that pattern holds, the Republican Party will win back their majority in the U.S. House of Representatives, if not also the U.S. Senate. The Democrats are especially vulnerable this year because the national mood is as bad, if not worse, than it has been in any recent midterm election year. It is possible the Democrats may not lose nearly as many seats as in the 1994 and 2010 elections, but that would be more a reflection of their narrow House majority heading into the elections than it would be of Americans' frustrations with the nation at a time when Democrats control the elected branches of the federal government.

The wild card in midterm elections is voter turnout. Historically, Republicans have had a structural advantage in midterm years because Republicans have been more likely than Democrats to vote. However, that advantage wasn't present in 2018, and ║┌┴¤═°'s new data suggest neither party currently has an advantage in attention to the campaigns, which is often a key indicator of turnout.

To stay up to date with the latest ║┌┴¤═° ║┌┴¤═° insights and updates, .

Learn more about how the works.