The pandemic has created new challenges for the women of Europe. How have things changed for them in recent years? Is domestic violence on the rise? Galina Zapryanova, ������'s regional research director for Eastern Europe and former Soviet states, joins the podcast to discuss new and preexisting hardships for European women, as well as the hopeful signs she sees.

Below is a full transcript of the conversation, including time stamps. Full audio is posted above.

Mohamed Younis 00:07

For ������, I'm Mohamed Younis, and this is the ������ Podcast. In this first of our two-part series commemorating International Women's Day, we take a close look at the challenges and opportunities facing women across Europe in a conversation that might challenge some of our preconceived notions about the experience of women across the continent. Galina Zapryanova is ������'s regional director of research for Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union region. Galina, welcome to the podcast.

Galina Zapryanova 00:37

Hi, Mo. Thank you. It's good to be here.

Mohamed Younis 00:39

The pandemic has certainly amplified many preexisting challenges, including ones faced by women and girls across the world. I wanted to talk to you, Galina, because you lead our research, particularly in Eastern Europe, where this topic of the role of women, the experience of women has really been a focus and our data has highlighted some really critical findings this year. Let me ask you first, what have we found from talking to women across Europe, and how have women's lives been affected by the pandemic?

Galina Zapryanova 01:09

Yeah, most of the research from the region indicates that the pandemic put increased pressure on women and girls, and there are several fronts in which this happened. There's the financial and professional, and then there's the personal. So, first of all, the pandemic-related lockdowns and business closures, they brought a sense of financial hardship and loss of income for those employees and affected occupations, as we know. This had a particularly negative impact on low-income families and women employed in the service industry and seasonal occupations. And then on the other hand, for women employed in industries that do allow for remote work, employment and income losses have been less severe, but they're experiencing still an increase in unpaid household work, child care challenges and remote schooling. As we know, it's tough on parents around the world in any country, but it appears to be particularly tough on working mothers in lower-income countries, especially in countries like the ones in FSU, in Eastern Europe, parts of it at least, that have more traditional family dynamics. So, with this type of extended school closures, this is something that has been a very new challenge brought by the pandemic that rarely existed before that.

Galina Zapryanova 02:22

When I was growing up in Bulgaria, I remember schools would sometimes close for one or two weeks in winter, the peak of the flu season, for what we as kids back then, we'll call … I would call it the flu vacation, even though it wasn't much of a vacation for our parents of course. Yes, but that was, you know, once per year, once per winter, one or two weeks. And then with COVID-19 you have especially in the first year of the pandemic, you have these closures on a very prolonged or cyclical basis. Open for a few weeks, then closed again, you know, and so on and so forth, and this new normal I think caught everyone unprepared. In some low-income countries or rural areas, remote learning may not even be a possibility to begin with. So these sort of school closures are feared to potentially cause some sort of delays or gaps in children's education and put stress on caretakers at home, which are usually women. And places where remote school is possible from a technological and resource standpoint, then we found that there's … we see that there is a disproportionate burden placed on mothers of young children to act as secondary teachers at home. So when you have women being the … expected to be the primary caregivers and household managers, while also holding a full-time job remotely because of the necessity of two incomes, then this usually negatively affects mothers' mental and physical health.

Galina Zapryanova 03:50

And one way we see this, for example, in our data is, is in terms of the dissatisfaction with the overall quality of healthcare available to them. Among the original rankings on the Hologic Global Women's Health Index, which is a multiyear comprehensive survey on women's health that first fielded in 2020, we see that Eastern Europe actually scores lower than the rest of Europe on most of the dimensions of health. For example, the majority of women in Eastern Europe were dissatisfied with the availability of quality healthcare in the area where they live, and they were also … women in Eastern Europe were also more likely to be dissatisfied with pregnancy care and more likely to experience health problems. So you can see how this, this kind of dissatisfaction with the availability of healthcare combined with the stress of the pandemic, the increased child care and financial stress, really put a lot of pressure on women in the region. And that is something we're seeing in the data.

Mohamed Younis 04:55

We've also seen some backsliding in perceptions of whether people in general in society across Eastern Europe think women are treated with respect. This is a question, of course, we ask all over the world. In your region, Galina, Poland and Slovakia lead the world in declines, which really stands out from your part of the world and the focus of your work with the World Poll. Can you describe a little bit for us what's going on, particularly in those two countries?

Galina Zapryanova 05:22

Yes, sure. So, in Poland and Slovakia, yeah, you're right. It is pretty noteworthy, the decline, what you've seen in the past couple of years. What we're seeing there, I think, is that in addition to the traditional, the so-called traditional pandemic-related challenges like financial insecurity, child care, mental stress … in addition to all these issues that are common to all countries, in Poland, Slovakia, we have seen some attempts by political parties to roll back abortion rights and restrict women's reproductive choices. So, for example, in Slovakia, these attempts were narrowly rejected in Parliament by just, by only one vote, after sparking some widespread protests and criticism from women's rights organizations. But then you have Poland, on the other hand, where a new total abortion ban was indeed successfully passed. And the ruling, in essence, it made Poland on the list of one of the countries with the most restrictive abortion laws. When it came into effect in 2021, since then, basically abortion is legal only in cases of incest, rape and when the life or health of the mother is in danger. And medical personnel performing abortions in any other circumstance can even be legally liable and subjected to criminal penalties.

Mohamed Younis 06:46

Let me ask you, Galina … we know that incidents of domestic violence have risen here in the U.S. during the pandemic. Are we seeing anything similar in Eastern Europe?

Galina Zapryanova 06:56

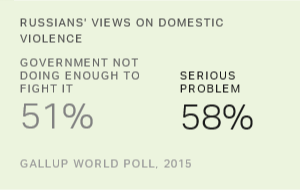

Yes. Unfortunately, domestic violence continues to be a serious problem in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. Even before the pandemic, ������ data did show that domestic violence was viewed as a serious problem in many countries in the region. Russia, for example, still doesn't have a domestic violence law that criminalizes domestic violence, despite most other countries already having at least, at the minimum, taken those, that legal measure to criminalize such violence. But aside from the legal baseline, also more informal help like the availability of shelters, resources, NGOs or just, just even someone to talk to like a helpline. A lot of these resources in, in these countries are quite minimal, especially in the former Soviet Union. And then you add COVID-19 to the mix and the various extended quarantines and movement restrictions that were necessitated by public health. So most research from around the world, then, show that … has shown reports that this resulted in increased physical and emotional stress for many people. And in this kind of environment when people are anxious and stressed and locked down together, maybe the ones who are in an abusive relationship, then, domestic violence is even more likely to occur. And with that, we'll be seeing reports and concerns about this as far as women in Eastern Europe and FSU.

Galina Zapryanova 08:24

Something we've seen in ������'s data also is that as part of the Hologic study on global women's health, we asked the women and men again about the scope of the problem in their country. So we asked them how widespread they think domestic violence is. And during the first year of data collection in 2020, when you look at the data globally, then two in three women aged 15 and older said that domestic violence is a widespread problem in their country. For Eastern Europe and FSU as a region, compared to the rest of the world, they were not on top of this ranking in the sense that they were not among the regions, as you said, were the highest percentage of proportions that said that domestic violence is widespread. But what stood out to me more in that data, actually, from my region, is the gap in perceptions between men and women in many FSU countries, in Eastern Europe countries. If you look at just the 20 countries around the world with the highest gap in perceptions of how widespread domestic violence is, then 12 out of those 20 countries are from Eastern Europe or the former Soviet Union.

Galina Zapryanova 09:34

And, I mean, we can hypothesize about various reasons why that could be the case. But I think such a systematic gender gap in terms of how widespread domestic violence is, it points to something more cultural, I think, still going on beyond the need for policy improvements and formal responses. I think there's still some lingering social norms, probably a post-Soviet legacy about talking about these topics. It is considered sometimes inappropriate or a private matter or a family matter. And women may not be able to speak up as often about it in public or raise awareness about such issues. So this results in a big chunk of these societies being unaware of how widespread this issue might even be, let alone trying to address it. Because the first step toward addressing something is being aware that it's a problem, right?

Mohamed Younis 10:31

Yeah. And it's, it's really important to keep in mind, as you said, that many of the data from this region actually highlight a preexisting challenge on this topic. And clearly, as appears it has done in the region, as it has done here in the U.S. and across many high- and low-income countries, it's, the pandemic has only exacerbated that challenge in many households, unfortunately. Galina, I want to end on a hopeful note or a positive note. Tell me about some of the positive changes you're seeing for women in the region.

Galina Zapryanova 11:05

Yes, that, that is a good note to end on. I would say, I would say that on this, that while the pandemic may have slowed down the progress -- only temporarily, I hope -- I would say that women in the region, they continue to do very well in educational and professional attainment. The public attitudes toward working women, female managers, female political leaders are largely positive, as we have seen over the years. For example, in 2019, ������ asked women and men in many countries around the world, not just Eastern Europe, some questions about women's leadership in politics and in the workplace, opportunities for education. And in Eastern Europe, we saw that a median of 60%, about 60% of the respondents said that it's quite possible for a woman to lead their country in the next 10 years, and only about 20% said that it is not possible. And in a lot of these countries, already at the time of the survey, a woman had served as a president or prime minister or was currently serving as one of these at the time. Similarly, when we asked about female, just female or male managers or if the respondents had any preference in terms of who's their manager, then the media in the majority of the countries was no preference about the gender of their manager, and this was true for both male and female respondents.

Mohamed Younis 12:35

So, hope in the future of the working woman.

Galina Zapryanova 12:38

Yeah, yes, definitely. I think that while the pandemic created some challenges for women in that sphere in terms of juggling work-life balance and child care, then still the access to jobs and attitudes toward women in the workplace is quite positive, I think, and fairly egalitarian. And you could say that women are getting things done and getting credit for it.

Mohamed Younis 13:00

That's, that's an awesome note to end on. Galina Zapryanova is ������'s regional director for research for Eastern Europe. Galina, thanks for being with us on the podcast. Thank you. That's our show. Thank you for tuning in. To subscribe and stay up to date with our latest conversations, just search for "The ������ Podcast" wherever you podcast. And for more key findings from ������ ������, go to news.gallup.com or follow us on Twitter @gallupnews. If you have suggestions for the show, email podcast@gallup.com. The ������ Podcast is directed by Curtis Grubb and produced by Justin McCarthy. I'm Mohamed Younis, and this is ������: reporting on the will of the people since the 1930s.