The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) is not turning out like President Donald Trump and the Republicans hoped it would -- at least, based on the public opinion data we have to date. Americans remain more likely to disapprove than approve of the law, with 40% approval and 49% disapproval in ║┌┴¤═°'s latest update. Other recent polls confirm that the tax reform law is viewed more negatively than positively -- including surveys conducted by the (36% approve/49% disapprove), (34% approve/43% disapprove), and (34% support/40% oppose).

Shortly after the law was passed, "set off a tidal wave of good news that continues to grow every single day," and he more recently re-emphasized : "We promised that these tax cuts would be rocket fuel for the American economy, and we were absolutely right."

But the public remains less than enthusiastic. Here are five reasons why:

1. Partisanship

The law was created by and highly identified with Trump and the Republicans; not one Democratic member of the House or the Senate voted in favor of the bill. This extreme partisanship is evident in views of the bill across partisan groups. As my colleague Megan Brennan found in ║┌┴¤═°'s most recent update on taxes: "Democrats' approval of the law is 16% and Republicans' is 78%. Independents' approval stands at 32%."

The remarkable impact of partisanship these days means that Republicans and Democrats look at much of what is going on around them (and to a degree what is going on in their personal lives) through the lens of their party affiliation. The tax situation is no different. Republicans extol the virtues of the new law, while Democrats decry it. With these baked-in attitudes, it becomes difficult for the law to gain majority approval.

2. Americans are confused about changes in their taxes and find it hard to compute the new law's impact.

║┌┴¤═°'s data show that 43% of Americans are unsure how the 2017 bill affected their taxes. Pew research similarly shows that on their taxes -- and that only 26% of Americans say they understand the new tax law "very well."

In reality, taxes did go down for the majority of Americans in 2018 as a result of the new law, and few saw them go up. As the : "About 65% of households paid less in individual income taxes in 2018 as a result of the TCJA. About 6% paid more. The rest paid about the same."

However, and this is a real key, there is no evidence of widespread recognition of this reality on Americans' part. In addition to those who can't say what effect the law had, ║┌┴¤═°'s latest survey shows that 21% of Americans say their taxes went up in 2018, compared with only 14% who say their taxes went down (21% say they stayed the same). A number of other surveys show the same type of result.

Part of this no doubt has to do with Americans' confusing their tax refunds with what they actually paid in taxes in 2018 (two significantly different things). The IRS adjusted workers' withholding in 2018 to take the new law into account, meaning that many Americans had a reduction in withholding from their paychecks in 2018. As a result, many got smaller refunds when they filed their taxes in 2019. This is a good thing in principle, according to experts (why loan the government money all year and receive no interest?) but many Americans may believe that getting a lower refund equates with having paid more in taxes.

Had the IRS not adjusted withholding in 2018, Americans would have gotten larger refunds than they were used to this year, which might in turn have led to a more positive view of the impact of the new law.

3. Americans were not all that enthusiastic about the new tax law to begin with.

There is little evidence that Americans were clamoring for a new tax law in 2017 before it was passed. The tax law received a very negative reading from the public in early December 2017, and, as I have noted, Americans have been negative about it ever since. Trump and Republican leaders have been unable to alter these apparently set-in-stone attitudes; the public as a whole remains negative.

All of this arises out of Americans' complex set of attitudes about taxes. Americans in recent years have generally been divided on whether the amount they pay in taxes is too high, about right or too low, although the "too high" percentage went up in 2016 and has edged down for the past two years. At the same time, a majority have continued to report that the amount they pay in taxes is fair.

My reading of these and other data is that -- everything else being equal -- Americans are OK with the concept of cutting taxes. In January 2017, in fact, "reduc[ing] income taxes for all Americans" scored high on the list for priorities for the new Trump administration. But despite this positive reaction to the general idea of cutting taxes, we have little evidence that taxes are a pressing priority based on open-ended, top-of-mind data. At no point in all of 2017 did more than 2% of Americans mention taxes as the most important problem facing the nation. Taxes have not appeared in "most important problem" lists in any significant way in years.

So, while the general idea of cutting taxes resonates with a reasonable percentage of the population, and while slightly more than half of Americans said their taxes were too high in 2017, these underlying sentiments did not result (and have not resulted) in strong approbation for the TCJA. Americans were negative on the law before Congress voted on it in late 2017, and once established, these views haven't moved much since.

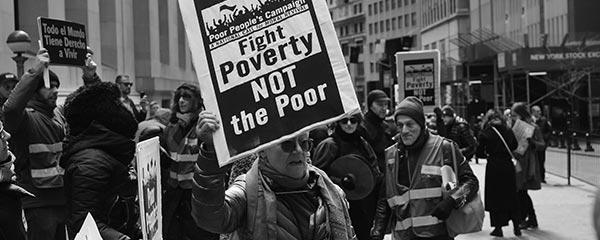

4. Americans are not convinced that tax cuts for the rich and for corporations are beneficial.

A majority of Americans have long believed that upper-income Americans and corporations pay too little in taxes. Did the new law address this situation? Americans say "no." Polling evidence shows that Americans (correctly) perceived that the law did little to change this and in fact benefited corporations and the rich.

-

A CNBC poll in March found that Americans were about seven times as likely to say the federal tax cut benefited large corporations a lot as they were to say it benefited them personally a lot (48% vs. 7%). Almost half of Americans said the new tax law had not benefited them at all, compared with only 7% who said it had not benefited large corporations.

- A CBS ║┌┴¤═° poll found that , while a much smaller percentage said the tax law had made their own taxes go down.

-

And a Pew Research poll conducted in late March showed that Americans were than they were about the amount they paid themselves.

To be sure, tax-law supporters didn't claim the law would increase taxes on the rich and on corporations, but rather argued that cuts in taxes for these groups would in classic trickle-down fashion produce broad economic benefits.

And, since the bill's passage, the economy has been strong. There has been more hiring and reduced unemployment, and the stock market has risen to new heights. ║┌┴¤═° data show that Americans have recognized the increasingly positive economy over the past several years, and have seen a much-improved job market.

But we don't have evidence that the public believes the tax law's cuts in taxes for corporations and the rich were directly responsible for these economic improvements. It appears difficult to get the average American to buy into the idea that everyone benefits from giving more money to large corporations (about which the public tends to hold quite negative attitudes) and to their already well-paid executives. Trump and the Republicans have apparently failed to connect these dots in the minds of the average American, dampening potential approval for the TCJA.

5. The tax bill did not address the huge elephant in the room: massive citizen distrust of government.

Americans have great distrust and lack of confidence in government. One might think that giving government less money in taxes fits in with those sentiments (that is, sending less money to a government they distrust), but I think it's more complex than that. Americans, in my view, are as interested in how government spends the money it has as they are in incremental reductions in how much they send the government.

Keep in mind that the government and the way it operates is the No. 1 problem facing the nation, according to Americans, and has been, with a few exceptions, for several years now. By contrast, as I have noted, few Americans tell us that high taxes are the most important problem facing the nation.

So massive new legislation that mainly reduces taxes addresses only one side of the "money in-money out" equation. The TCJA does little to attempt to fix "money out" side -- the way the government uses the tax money it does get. Despite broad distrust of government, the public appreciates a lot of things government does, even if revenues are cut down somewhat through tax cuts.

The law thus missed the mark in addressing the public's priorities, and this is, I believe, part of the reason we find Americans more negative than positive when asked about the TCJA. Had the bill coupled tax cuts with changes in how government operates, the public likely would be more positive about it at this point in time.