The court trial now underway in federal district court in Boston, in which Asian-American students, represented by Students for Fair Admissions, are alleging discrimination on the part of Harvard University, highlights the extraordinary complexities that swirl around the broad issue of affirmative action. The key focus of the trial is the legality of taking applicants' racial and ethnic characteristics into account when making college admissions decisions. The issue also has relevance in the workplace, as critics focus on the disproportionality of individuals with certain racial and ethnic characteristics in high-reward roles in business.

The court case is based on the allegation that Harvard takes racial and ethnic characteristics into account in an effort to expand the representation of certain groups in the student body, while at the same time limiting the number of students with other racial and ethnic characteristics (Asian-Americans) to avoid their becoming a disproportionately large percentage of students.

Harvard is robustly defending its policies of sifting through more than 40,000 applications to decide on which 2,000 or so will be given the coveted acceptance letters. Harvard says that it takes into account many characteristics of applicants in its efforts to assemble a "holistically" superior student body.

The Public's Take on Issues of Race and Ethnicity in Hiring and Admissions

Public opinion on this broad issue of the use of race and ethnicity in making admissions and hiring decisions is as complex as the issues being fought in the court case. We need to consider the results of a number of different ways the issue has been addressed in research to arrive at an understanding of where the public stands on the issue.

║┌┴¤═° polls have shown that a majority -- although not a super majority -- of Americans favor the broad, conceptual idea of "affirmative action for racial minorities." Responses to this question are to some degree affected by the context in which it is asked, but our most recent updates show that 54% to 58% of the public favors affirmative action for racial minorities.

A focuses more specifically on college, asking about "affirmative action programs designed to increase the number of black and minority students on college campuses." Pew found 71% of Americans said that this was a good thing.

Neither of these questions explains what specific actions these affirmative action programs would involve. The ║┌┴¤═° question does not define "affirmative action" at all, leaving that to the understanding of the respondent. The Pew question doesn't define the specifics of the affirmative action programs beyond saying that the result would be to increase the number of black and minority students on college campuses.

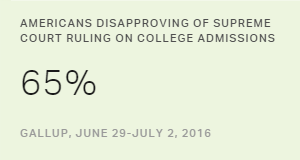

When specifics are outlined for respondents, support drops. In 2016, ║┌┴¤═°, in conjunction with Inside Higher Ed, asked a question about the then-recent Supreme Court decision in Fisher v. University of Texas, worded as follows: "The Supreme Court recently ruled on a case that confirms that colleges can consider the race or ethnicity of students when making decisions on who to admit to the college. Overall, do you approve or disapprove of the Supreme Court's decision?"

The results: 31% approval and 65% disapproval, a sharp reversal from what the broad affirmative action results show.

This result is underscored by answers to another question in the ║┌┴¤═°-Inside Higher Ed study. This interrogation gave Americans a list of nine different factors that colleges and universities may consider in making admissions decisions and asked the respondents to say if each should be a major factor, a minor factor or not a factor at all in college admissions.

The list was designed to encompass most of the types of things that selective college admissions officers say are potentially taken into account in the effort to produce a holistically diverse student body. These include grades, standardized test scores, the types of courses a student takes in high school, family economic circumstances, whether the student would be the first in the family to attend college, athletic ability, parental alumni status, race and ethnicity, and gender.

The public's opinion was clear. Majorities said that high school grades (73%) and scores on standardized tests (55%) should be major factors in college admissions, while 50% said that the types of courses the student took should be a major factor. Well less than half said any of the other six factors should be major considerations. This includes in particular race or ethnicity, which 9% of Americans believe should be a major factor, 27% a minor factor and 63% not a factor at all in college admissions.

The public, at least without further explanation or rationale, simply doesn't like the idea of colleges taking race or ethnicity into account in admissions decisions. Admissions decisions, the public is in essence saying, should be blind to the race and ethnicity of the applicant.

(The survey also included a measure of how well the respondents indicated that they understood the college admissions process. Those who said that they were most familiar with the college admissions process did not differ significantly from those who did not.)

The previous questions didn't attempt to explain the reasons why Harvard and other colleges might argue that it is now a good (or affirmative) thing to take race and ethnicity into account. These reasons include the idea that doing so helps compensate for historical discrimination and other cultural and social factors that affect grades and standardized test scores for certain groups, and also helps create a diverse student body.

A separate question ║┌┴¤═° has asked four times between 2003 and 2016 does provide an explanation for the two sides of this argument:

Which comes closer to your view about evaluating students for admission into a college or university -- [ROTATED: applicants should be admitted solely on the basis of merit, even if that results in few minority students being admitted (or) an applicant's racial and ethnic background should be considered to help promote diversity on college campuses, even if that means admitting some minority students who otherwise would not be admitted]?

The wording of this question can be debated, and some may argue that the two sides of the argument are not adequately represented. But the key is to consider how Americans react when they hear these specific arguments. And the answer to that is clear. Each of the four times ║┌┴¤═° has asked this question over a 13-year time period, between 67% and 70% of Americans chose the "solely on merit" option.

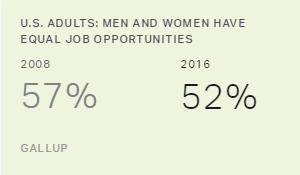

(We recently asked a variant of this question in terms of hiring for jobs and found the same pattern of results. Americans tilt strongly toward the idea of merit as the criteria for hiring, not race and ethnicity.)

Bottom Line: Americans and the Use of Race and Ethnicity in College Admissions

The most important conclusion from all of these data is that Americans do not like the idea of colleges using race and ethnicity as a factor in decisions on college admissions. This is true even when it is explained that this would help increase the diversity of the student body while admitting students who otherwise might not be admitted.

It's possible that Americans, in answering these questions about college admissions, are thinking of the historically negative discrimination practices based on individuals' racial and ethnic characteristics, practices that were made illegal by historic civil rights rulings and legislation in the 1950s and 1960s.

At the same time, the broader concept of affirmative action receives more positive reaction from Americans. The key then is what Americans are thinking of when they hear the words "affirmative action." Apparently it is not setting differential standards for admissions based on an applicant's race or ethnicity. It could be that affirmative action connotes to Americans an outreach that encourages more individuals with certain racial and ethnic characteristics to apply (something Harvard does). It could be that affirmative action connotes efforts to increase the high school preparation for individuals with certain racial and ethnic characteristics to put them in a more competitive position for admissions decisions. Or respondents could favor the idea simply because they applaud the result -- more diversity in a student body -- without thinking much about how that result is brought about.